Views of Your Commute

A series of digital, vector based screen prints that aims to visualise the culture of commuting across Auckland’s Emerging Public Transit Network.

August 24th, 2025

Benjamin Everitt

Special thanks to:

The organisers of Auckland Zinefest, Collectivo Narval, and F.Stop for setting up the platform for local artists to display their works at Toitu Studio One Ponsonby.

Outside of architectural drafting and teaching at Auckland University of Technology, I have been making digital illustrations of transit stations around the city of Auckland as a small contribution to share my passion for transit oriented design, urbanism, and wayfinding.

The visual language of wayfinding:

Let me ask you a question: how do you get around the city everyday?

Do you walk?

Catch the Bus? Drive?

Train?

Or even catch the Ferry?

Chances are there were many signs and markings that have guided you to your destination, as well as your own sense of direction and orienteering.

You may not realise it, but everyday you're constantly performing a minor miracle. You’re not just moving through space; you're wayfinding.

But what is wayfinding, really? And how do our brains manage to keep us from getting hopelessly, utterly lost in the vast, complex tapestry of our environments?

For centuries, philosophers and explorers pondered this. But it wasn't until the mid-20th century that an urban planner named Kevin Lynch gave us a groundbreaking insight. In his seminal 1960 book, The Image of the City, Lynch proposed that we don't just see cities; we map them. Not with paper and ink, but with something far more intricate: mental maps.

Lynch identified five key elements that form the bedrock of these internal navigational systems. Think of them as the fundamental building blocks our brains use to construct a legible, navigable world.

Paths:

First, Paths. These are the channels we move along: streets, sidewalks, rivers, even hallways in a building. They are the arteries of our mental maps, defining direction and flow. Imagine trying to navigate a city with no discernible paths – pure chaos.

Edges:

Then there are Edges. These are boundaries. Walls, coastlines, railway tracks, the edge of a park. They define limits, separate one area from another, and often act as barriers. They help us understand where one "place" ends and another begins.

Districts:

Next, Districts. These are medium-to-large areas with a recognizable character. Think of a financial district, a historic old town, or a vibrant arts quarter. We know we've "entered" them, and they offer a sense of identity and place within the larger urban fabric.

Nodes:

Crucially, we have Nodes. These are focal points, points of intense activity, where paths often converge. Major intersections, public squares, bustling train stations. They are the junctions, the hubs, the memorable spots where decisions are made. They are the sticky points in our mental maps.

Landmarks:

Finally, we have Landmarks. These are external points of reference. A distinctive building, a towering statue, a unique tree, a prominent sign. We don't enter them in the same way we enter districts or nodes, but they are vital external cues that help us orient ourselves and confirm our position.

Together, these five elements—Paths, Edges, Districts, Nodes, and Landmarks—allow our brains to create a coherent "image of the city." This image isn't necessarily a perfect, geometrically accurate map. Instead, it's a simplified, often distorted, but incredibly functional representation tailored to our needs and experiences.

Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. MIT Press.

Why does this matter?

Because a clear, legible mental map isn't just about finding your way to the nearest coffee shop. It impacts our sense of security, our emotional connection to a place, and even our cognitive load. When an environment is "imageable," when its elements are distinct and well-arranged, we feel more comfortable, more in control, and less stressed. We feel at home, even in unfamiliar territory.

In essence, Kevin Lynch showed us that successful wayfinding isn't just about signs and directions. It's about how the very structure of our environment speaks to our innate human need to understand, to organize, and to belong within the vast, beautiful, and sometimes bewildering spaces we inhabit. It's about the invisible maps that guide our lives, one confident step at a time.

The Multi-Modal Maze: When Transit Chains Our Journey

What happens when a single journey isn't a simple stroll down a path?

What happens when your destination demands not just walking, but chaining together a bus, a train, a ferry, and finally, renting a dangerously fast electric scooter for the last leg of the journey?

What happens to passengers with strollers, wheel chair users, or people who require assistance? Can they arrive at the same destination without encountering an obstacle?

Suddenly, our familiar navigational instincts, honed for singular journeys become challenged and convoluted.

Each transition between a bus stop, a train station, a ferry terminal, and a bike lane presents a unique challenge to our brain's mapping process. The very elements Kevin Lynch so brilliantly identified, the anchors of our mental maps, become fluid, sometimes frustratingly so.

This can be especially challenging for a city like Tamaki Makaurau Auckland that is planned around a complex topography of harbours, and multiple dormant volcanoes.

Paths still exist, of course, but they're no longer continuous. The clear trajectory of a bus route gives way to the distinct, often subterranean paths of a subway line. Then, having to navigate a pier of a ferry deck, followed by the specific, often unmarked paths of a bike lane. Our brain has to stitch together entirely different types of paths into one coherent journey.

Edges become less defined at transfer points. Is the bus stop the edge of the street, or the edge of our next transit segment? The sharp distinction between, say, a pedestrian zone and a rail line blurs at these complex nodes. Our brains are constantly re-evaluating where one "system" ends and another begins.

Districts dissolve into undifferentiated space, particularly within large transit hubs. How do you distinguish one "area" from another when every direction leads to a different mode of transport? The unique character that defines an urban neighborhood above ground is replaced by the uniform, often functional design of a transportation interchange...

and crucially, Nodes become paramount, but also overwhelming. These are the transfer points, the central nervous system of our multi-modal journey. A busy train station, where multiple lines converge, feeding into bus terminals and ferry links. They are points of intense decision-making. But if these nodes are poorly designed, with unclear signage or illogical layouts, they become points of stress and confusion rather than efficient hubs.

As for Landmarks, they become transient and context-dependent. The iconic building that guided you to the bus stop is irrelevant once you're underground on the subway. Here, landmarks are often smaller, more specific: a particular platform number, the name of a specific ferry, the sign for the bike-share station. Our brain must rapidly acquire and discard these localized cues with each new leg of the journey.

This constant shifting of perspective, this stitching together of disparate transit systems, demands significant cognitive effort. Our brains are not just mapping the physical space, but the system itself – the schedules, the connections, the unspoken rules of each mode. When an interchange is clear, well-signed, and logically laid out, the journey feels seamless. But when it's confusing, our mental map struggles, and the journey becomes a stressful puzzle.

Ultimately, successful multi-modal wayfinding isn't just about getting from A to B. It's about designing interconnected systems that resonate with how our brains naturally form these "images" of the city. It's about making each transition point a clear node, each waiting area a distinct district, and each change in path intuitively navigable. Because even when we're chaining together buses, trains, ferries, and bikes, our brains crave clarity, yearning to know: "Where am I in this system? And how do I connect to the next one?"

This understanding of our mental maps is vividly apparent in the beating hearts of the world's great metropolises. Cities like London, Paris, Tokyo, and New York didn't just build vast public transportation networks; they built systems of legibility.

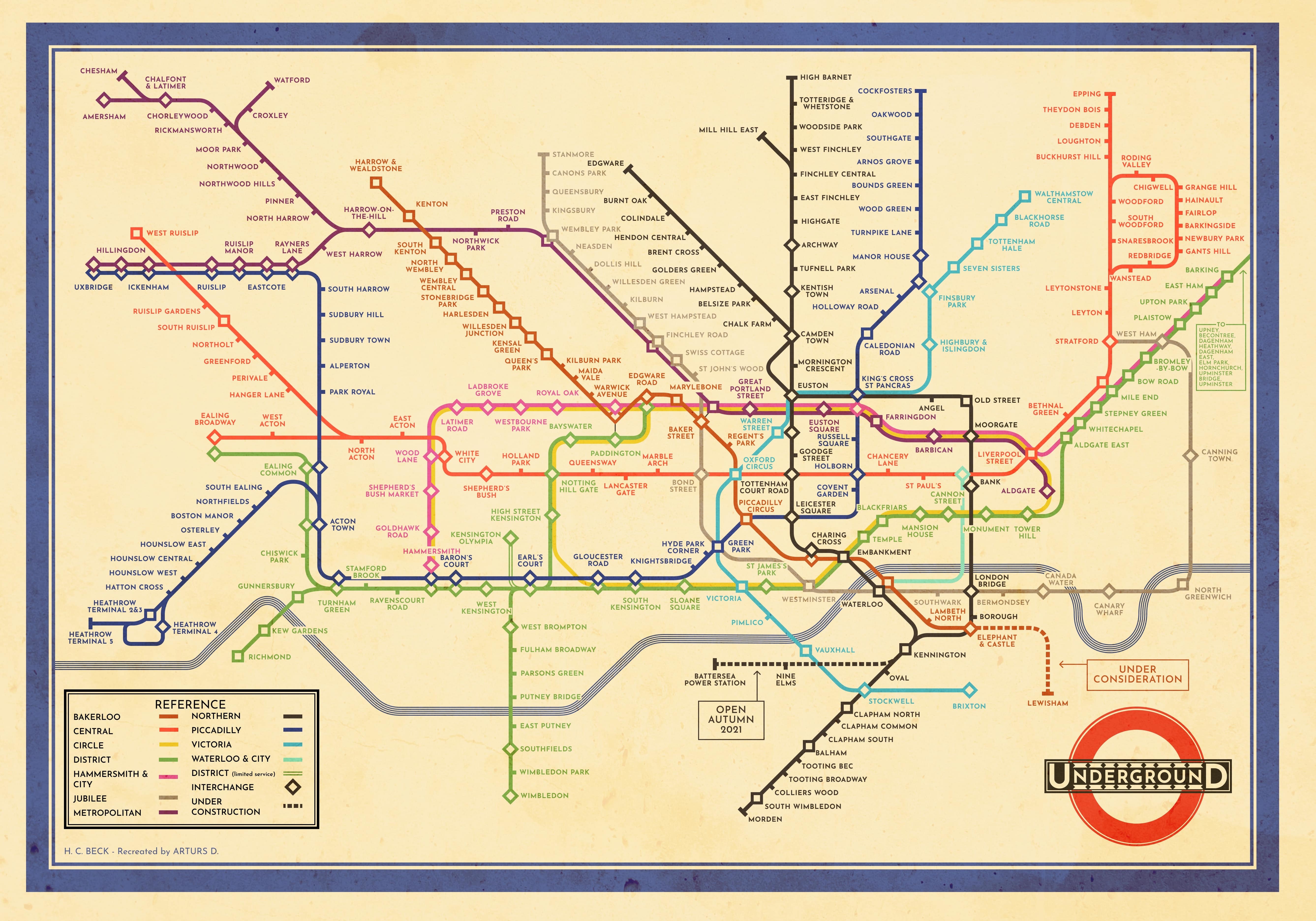

Consider the legendary London Underground map, first designed by Harry Beck. It's a masterpiece of wayfinding. It deliberately distorts geographical accuracy to simplify paths into straight lines, making complex interchanges clear nodes. The consistent visual language—the iconic roundel, the distinct line colors—acts as an enormous landmark system, effortlessly guiding millions through a subterranean labyrinth.

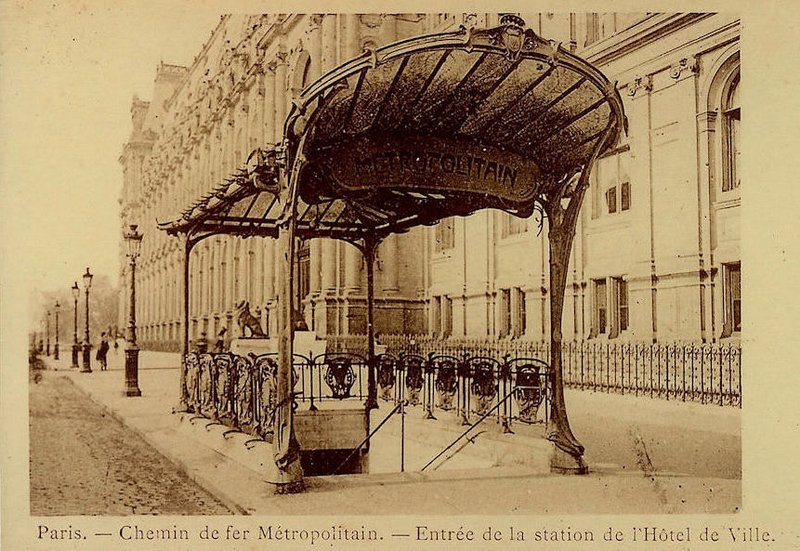

Paris, with its distinct Art Nouveau entrances designed by Architect Hector Guimard were made to look aesthetically pleasing and inviting to passengers as possible. It creates a strong sense of place for the city, as even the most mundane object, a bench, bin, or lamp post is immediately recognisable as ‘Parisan’.

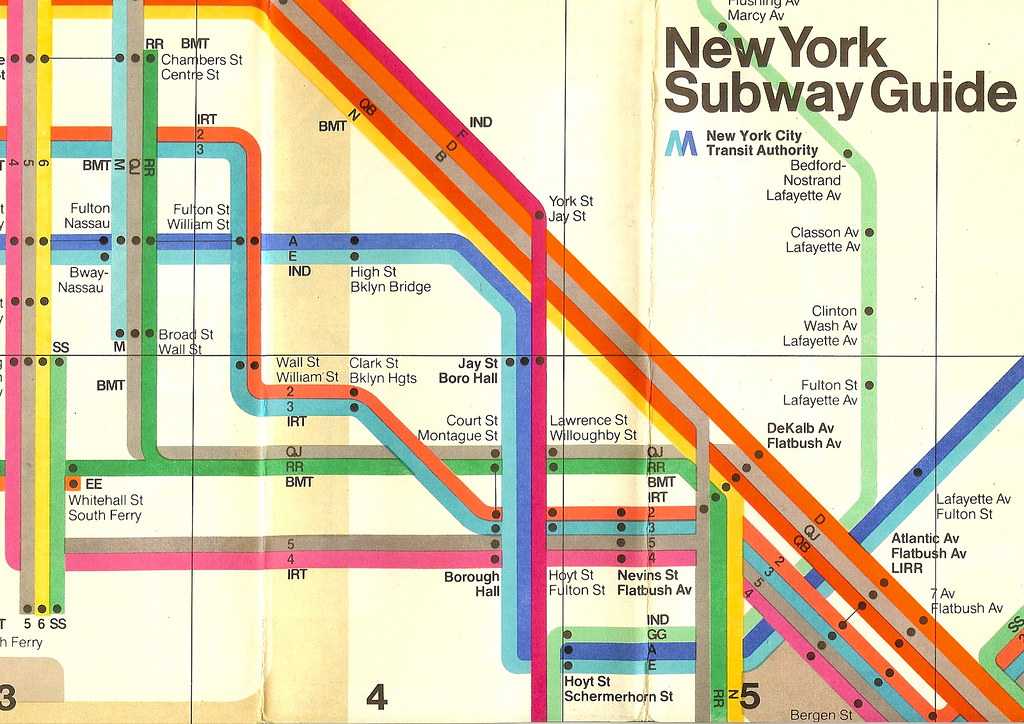

New York Metro Map design was once very similar to that of Londons, but an issue was presented in the 1970s where the subway was so dangerous, people needed to reach the surface of the city as quickly as possible. This led to a complete redesign of the subway line map, where the nodes of each station were no longer abstracted, but drawn accurately to match the station exits with the roads that passengers were surfacing.

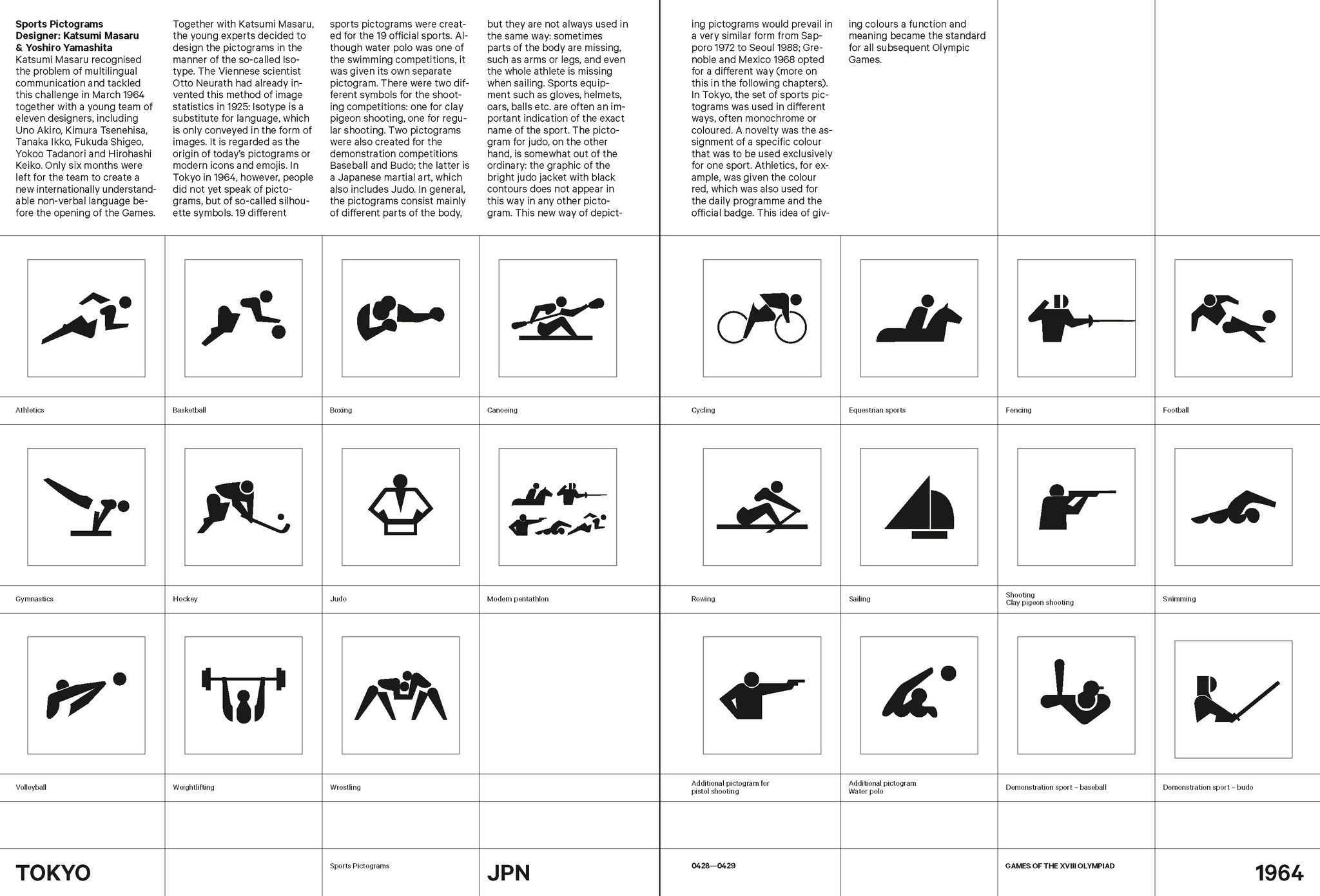

The Tokyo Metro faced another issue in the 1960s, whereby Japan was opening up its post war city to the rest of the world as it hosted the 1964 Olympics. To ensure the city felt accommodating to people and reduce the language barrier, pictograms were invented to symbolise the locations of key services using universally recognisable icons, such as toilets, kiosks, ticketing, and transfer stations.=

These cities have perfected the art of creating an "image of the city" not just on the surface, but within their complex transit arteries. Their success has resonated globally, becoming the gold standard, inspiring the design of public transportation systems in countless other urban centers...

but the story doesn't end there. All around the world, particularly in newer, rapidly developing cities like in Tamaki Makaurau Auckland, a profound shift is underway. For decades, many urban areas grew around the car, designing paths primarily for vehicles and creating vast, undifferentiated districts of asphalt.

Now, these cities are actively building new infrastructure, meticulously crafting networks designed to move people, not just cars. They're constructing interconnected bus rapid transit lines, expanding subway systems, creating dedicated bike lanes, and even integrating ferry services into a seamless multi-modal experience.

This transition from car-centric planning presents a phenomenal, unprecedented opportunity for visual designers. It's a blank canvas where they can apply Kevin Lynch's principles with a fresh perspective. It's not just about pointing the way; it's about telling a story.

Designers can use color, typography, architectural elements, and even soundscapes to define new districts within the transit network, to highlight crucial nodes, and to establish clear, memorable landmarks that are intrinsically linked to the journey itself. They can craft a visual narrative that reassures, informs, and ultimately, empowers.

The future of wayfinding isn't just about maps; it's about creating immersive, intuitive experiences. It's about building a sense of place and understanding even as we chain together buses, trains, ferries, and bikes. It's about the invisible maps in our minds, constantly evolving, constantly connecting us to the vast, intricate, and ever-growing tapestry of our cities...

But even with grand visions, daily reality presents its own intricate puzzles. Here in Tamaki Makaurau Auckland, for instance, the growing public transport network, while vital, often throws up unique wayfinding challenges. Imagine someone with an ailment, unable to drive, needing to catch a bus to their local clinic. Then, their GP refers them to a specialist across town – suddenly, navigating to an unfamiliar district, finding the right series of connections, perhaps from bus to train, or even an AT HOP ferry, becomes a complex mental exercise. What are the right nodes for transfer? Where are the reliable landmarks in this new part of the city? Or consider a professional whose job demands visiting multiple clients across town, constantly re-mapping their journey. Friends on opposite sides of the Waitematā Harbour, wanting to meet for a beer, face their own transit riddle. Even for young adults, without the freedom of a car, getting to a part-time job often means deciphering fragmented paths and multiple transfers, all while racing against the clock. These aren't just logistical hurdles; they're daily tests of our mental maps, pushing our cognitive limits to stitch together a coherent journey from disparate pieces.

Wayfinding is more than just an allocation of signage. It is about curating an experience that empowers people to traverse the city smoothly, and experience the city as a flow of public life. When we think about living in our ‘dream city’, it might not be shaped by the size, or the population, but rather how much we can experience and enjoy our lives. One possible way for people to enjoy their lives to their absolute fullest in the city that they live in, is to provide a collective, mental map through districts, streets, and buildings for everyone to navigate their way towards. This is how we can begin to craft the image of the city.

“True enough, we need an environment which is not simply well organized, but poetic and symbolic as well... By appearing as a remarkable and well-knit place, the city could provide a ground for the clustering and organization of these meanings and associations. Such a sense of place in itself enhances every human activity that occurs there, and encourages the deposit of a memory trace.”

― Kevin Lynch, The image of the city

You can read a full copy of Lynch’s book here. (Courtesy of MIT Press)

Thank you to Auckland City Council, for your commitment to fostering inclusive public spaces like Toitū Studio One Ponsonby.

The opportunity to exhibit my work in such a welcoming communal gallery has been invaluable. Without access to a space like this, it would not have been possible to explore the art of public exhibition and learn how to present my creations in a way that resonates with a wider audience. The council’s dedication to providing accessible venues is not only a benefit to artists but also enriches the entire community, making art a shared experience for all. This initiative has been crucial in my journey as an artist, and I am deeply grateful for your support.

Please visit https://www.studioone.org.nz/ for future public events.